Biodegradable & compostable

They are two of the most frequently misunderstood words associated with eco-friendly claims and manufactured products. So learning how manufacturers use – and misuse – these words can help us cut through greenwashing.

Biodegradable vs compostable – understanding the difference

The term ‘biodegradable’ is everywhere. The word is assuring – after all ‘bio’ means life, and ‘degradable’ is what we are seeking in a world where rubbish hangs around for way too long, in all the wrong places.

‘Compostable’ is even cosier. It promises we can turn our waste into an earthy, nutrient-rich plant tonic – right in our own home garden.

The problem is that the definitions for these words can vary, depending on their use. Almost everything will degrade given enough time. And ‘compostable’ waste might be the last thing you’d want in your compost bin.

Understanding what we mean when we add ‘bio’ to ‘degrade’ or ‘industrial’ to ‘composting’ helps us make better decisions about the materials we buy – particularly plastics.

Given that the bulk of a flower purchase is naturally compostable, it makes sense that the products we use to go with our flowers work with all composting systems and don’t end up as waste.

Biodegradable

Biodegradability is the ability of a material to degrade through the action of living organisms such as bacteria or fungi. These organisms use the material as a source of energy to grow. In the process of being ‘consumed’, the material breaks into smaller and smaller pieces. Eventually, all the energy-containing compounds are used up.

Light, heat, presence of oxygen and moisture levels all impact the rate of biodegradation.

Biodegradability happens in stages. Everyone is familiar with that experience of finding a container of leftover food in the fridge. With all good intentions, we put some unused rice away for tomorrow. Then new shopping pushes it to a back corner, way out of sight.

A few weeks later, the rice is covered with colourful blotches of bacteria and mould. The spores for these came from the air and landed on the rice before it went in the fridge. When the rice started to deteriorate, those spores had a chance to start growing.

Because fridges are cold, and cold slows down the rate of biodegradation, the process of complete degradation might take a very long time, possibly even a year or two. At that point, the mould and bacteria colonies have consumed their easy meal, and we’ll have a container of alien-like gunk. What was once some handy leftovers has now completely transformed by living organisms. One hundred percent biodegradability has been achieved – there is not a single speck of rice left.

Composting

Composting is a human-driven process for managing organic waste that employs biodegradation to do the hard work. It uses the same biological process that turns fallen leaf litter into new soil.

Take our leftover rice. If we dump it in our home compost system instead of the fridge, it will biodegrade far more rapidly. Conditions are warm, and there are many more microscopic organisms – plus small animals like worms and insects – ready to use the rice as an energy source. In these conditions, the rice might completely disappear in a few weeks.

Healthy compost is a mix of things, all of them natural. It includes organic matter such as worm castings, nutrients and beneficial organisms that are important for healthy soil. As the ingredients biodegrade, gases are released, but unlike in nature, the release of these gases can be managed to a degree. The type of gas released is determined by the composting conditions.

Aerobic and anaerobic

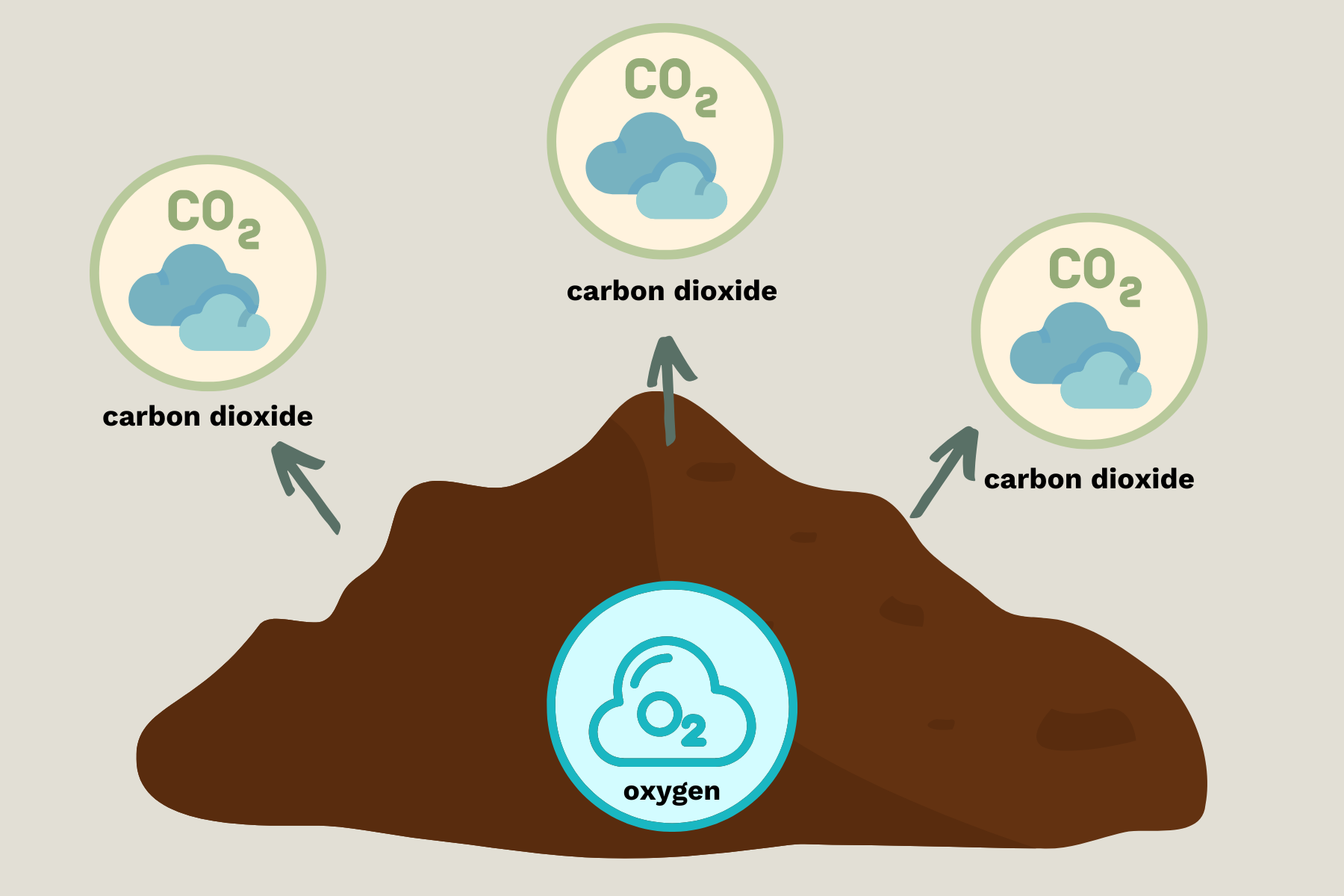

When composting happens with oxygen present it is called ‘aerobic biodegradation’. In these conditions, the gas by-product is carbon dioxide.

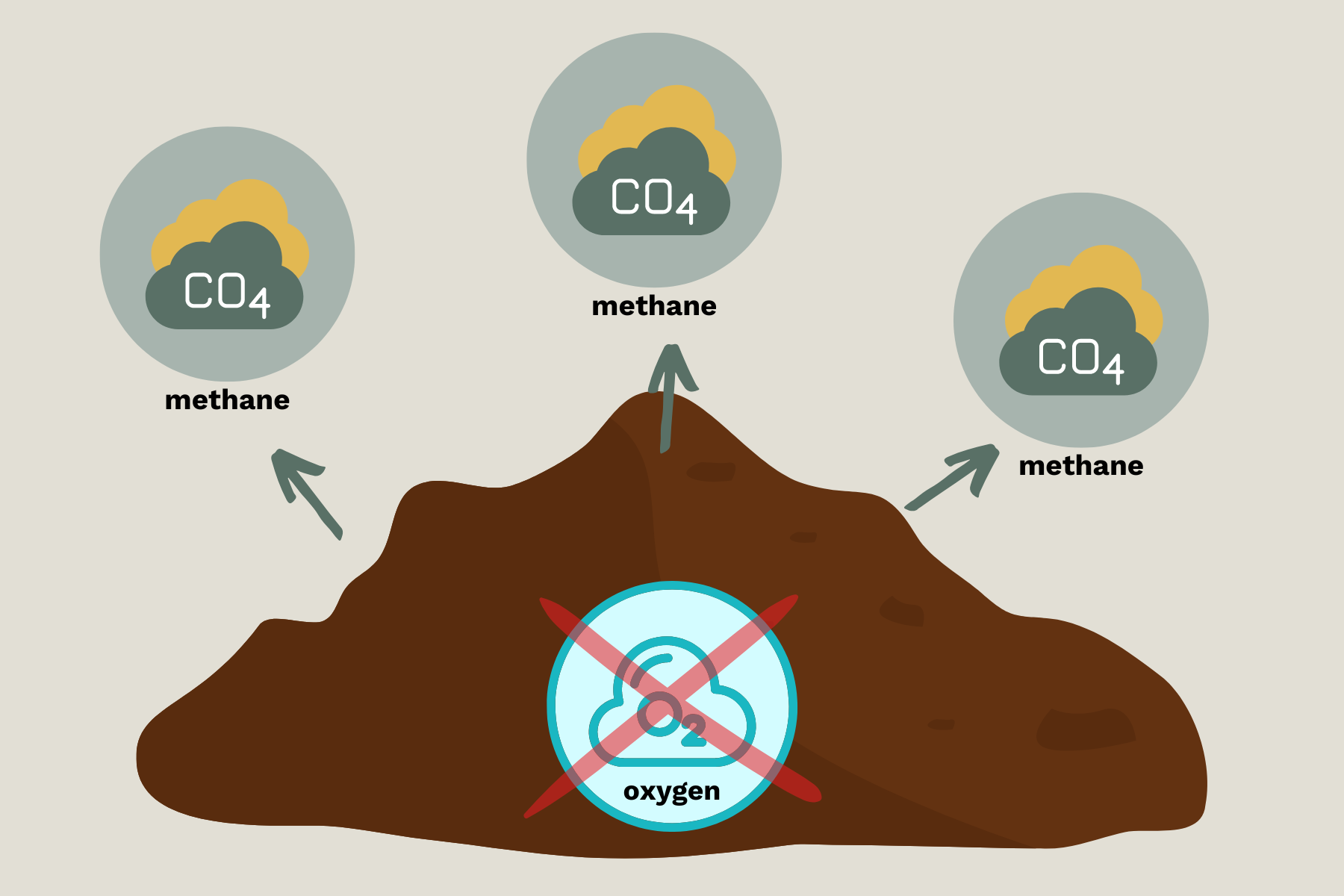

‘Anaerobic biodegradation’ occurs when the material degrades without oxygen. When anaerobic degradation takes place, for example in landfill, the gas released is methane – a greenhouse gas 25 times more potent than carbon dioxide. In some countries, industrial ‘anaerobic digesters’ are used to create methane for fuel.

Aerobic biodegradation takes place in the presence of oxygen and produces carbon dioxide as a gas.

Anaerobic biodegradation takes place without oxygen present. This results in methane being produced, instead of carbon dioxide. Methane is 25 x times more powerful than carbon dioxide as a greenhouse gas.

Home compostable

Both of these biodegradation processes – anerobic and anaerobic – can happen inside our home compost bin. If we look after our compost – turn it so it gets air, add brown matter (such as straw, dried leaves and plant prunings) so it doesn’t turn into a stinky, wet sludge – then we can maintain our compost aerobically. This means our compost won’t smell, we’ll optimise the conditions for producing nutrient-rich organic matter, and our neighbours won’t complain. And just as importantly, we’ll avoid producing methane.

Generally, most food scraps can go in a home compost system, although many people avoid cooked food and meat scraps because they attract vermin. Also, many plant-based manufactured materials can safely go in a compost such as paper, pure cotton fabric and egg cartons.

Industrial composting

If a manufactured product is certified ‘industrial compostable’, this means that the material needs to be in very specific, human-controlled conditions to break down. There are different types of industrial composting methods. Most rely on high temperatures to ensure that biodegradation takes place, and some rely on the addition of microbes to speed up the process.

So how does this all apply to plastics?

First of all, traditional plastics are made from petrochemicals and are generally not biodegradable. They will eventually break down (over hundreds or thousands of years) or degrade under influences like light, friction, heat or chemical interactions, but this process usually involves the material fragmenting into smaller and smaller pieces first. Once they are smaller than 5 millimetres in size, they are commonly referred to as microplastics.

Both plastics and microplastics are everywhere, including in our rainwater. They are a known threat to the health of humans and animals.

In an attempt to address the growing plastic pollution issue, and move away from the use of non-renewable petrochemicals, scientists and manufacturers have developed a new generation of plastic made from plant material – generally corn starch or sugar cane. These are called ‘bioplastics’.

Bioplastics

The important thing to remember is that not all bioplastics biodegrade in the same way.

‘Home compost’ certified.

Bioplastics include the soft caddy bags used to line compost bins. These can go in your compost bin if they have a stamp with a certification that clearly says ‘home-compostable’.

Different countries have slightly different standards for home composting. All require that the bioplastic breaks down at a specific rate in a fixed period of time, and without leaving any toxic residues.

These materials may be also accepted by some municipalities in some green waste recovery streams, but not all municipalities offer these services, and some countries are much further ahead with organic waste recovery than others. Everybody must check with their own municipality to determine what the local processes are regarding organic waste management.

‘Industrially compostable’ certified

Other bioplastics can go in industrial composting facilities only. These include things like take-away food containers, straws and other packaging items. These products usually carry a stamp that says: “industrial compostable only”. These require higher levels of heat, moisture and exposure in composting conditions to degrade.

At present, most waste systems are not set up to capture industrially compostable bioplastics. For instance, there is no system for collection or processing of compostable plastic in the UK.

The problem with ‘biodegradable’ plastics is that they are not necessarily a solution to the plastic crisis.

In some ways bioplastics sound like a solution, but there are multiple problems with bioplastics.

Firstly, not all plant-based plastics are biodegradable. To make it even more confusing, some petrochemical-based plastics are biodegradable (but of course, not renewable).

Secondly, some products marketed as bioplastics – or as a greener alternative to regular plastic – contain a mix of plant material and petrochemicals. This is positive because it is a shift towards using renewable resources, but the product may take just as long to break down, and be just as polluting, as regular plastic.

Thirdly, most bioplastics need very specific conditions to break down – generally, an industrial composter. Some waste processing centres have this capability, but if not, the products must go to landfill or incineration.

Without this specific industrial treatment, bioplastics can hang around in the environment – especially the marine environment – for a very long time, causing problems for animal, human and planetary health.

So what plastic should we choose?

The main messages remain the same – avoid plastic as much as you can.

When considering bioplastics, examine the product carefully. Think about how you (or a client) will dispose of this product, and let that guide your choice, remembering that in many places, access to industrial composting facilities is limited.

When buying sundries (bag, wrap, ties), home-compostable products are the best choice for the environment. They can go in both home-composting systems, and industrial systems.

Given that the bulk of a flower purchase is naturally compostable, it makes sense that the products we use to go with our flowers work with all composting systems and don’t end up as waste.